Lecture Series 1: Ancient vs. Modern Regimes – Course Description

Shakespeare’s profound understanding of human nature was grounded in his profound understanding of politics. He would not have been able to portray such a wide variety of human types if he had not been aware of the wide variety of political conditions in which people have lived over the centuries and of how these different regimes work to shape character. For example, Shakespeare understands how living in a monarchy differs from living in a republic—not just in terms of the political choices people make but also in terms of their fundamental outlook on life.

In this course, we study the variety of political settings of Shakespeare’s plays and relate his political insights to his insights into human nature. We focus on Shakespeare’s understanding of the ancient Roman regime, and its alternatives in what for him was the modern Christian world. The power and endurance of Rome’s political institutions have deeply impressed people over the centuries, and understanding how and why they functioned so well has been a perennial question for political thinkers. Some of the most important modern political philosophers have developed their ideas in the form of meditations on Roman history. Issues such as the nature of a republic and its mixed regime, the dynamics of empire, the relation between domestic and foreign policy, the role of religion in politics, and the limits of politics—all have been explored by looking at the experience of Rome.

Shakespeare did as much as any writer to shape our image of ancient Rome, and he did a remarkable job of accurately reflecting the changing nature of Rome and its institutions. We will discuss his principal plays devoted to Rome, not in the order in which they were written, but in historical order, from the early days of the Republic in Coriolanus through the crisis of the Republic in Julius Caesar to the emergence of the imperial system in Antony and Cleopatra. We will focus on Shakespeare’s sense of the changing Roman regime, especially the epochal break between the Republic and the Empire. In Henry V, The Merchant of Venice, Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth we will study the ways in which Roman traditions survived into the modern world, and how the altered terms of a Christian cosmos affect political life for Shakespeare’s heroes and, in particular, create a new basis for tragedy. In The Merchant of Venice and Othello, we will study the revival of republicanism in the modern world, in the new form of the commercial republic.

Lecture Series 2: The Politics of Genre – Course Description

In the first set of lectures, the organizing principle was history. In this second set of lectures, the organizing principle is genre. We sample each of the principal genres Shakespeare worked in: English history, comedy, tragedy, and the peculiar form of his last plays, whether called tragicomedy or romance. The aim is to draw out the political implications of the genres Shakespeare employed.

We begin with Shakespeare’s Second Tetralogy of history plays: Richard II, Henry IV, Parts One and Two, and Henry V. Charting the movement from medieval to modern kingship, these plays offer one of Shakespeare’s most sustained enquiries into the nature of politics and the tension between public and private life. With tragic figures such as Hotspur and comic figures such as Falstaff, these history plays also raise the question of the relation between tragedy and comedy in Shakespeare. Throughout these lectures, we remain mindful of the remarkable fact that, almost alone among great playwrights, Shakespeare was able to move effortlessly between tragedy and comedy (often in the same play) and to triumph in either genre. What does this tell us about his art? And are his comedies as worthy as his tragedies of serious political consideration?

To sharpen our understanding of the nature of tragedy and comedy, we pair Romeo and Juliet with A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The two plays treat the same subject—young love—and their contrasting approaches to it highlight the differences between tragedy and comedy. In political terms, tragedy reunites a community only by excluding the characters who challenged its values, whereas comedy operates on inclusive principles, in the end reconciling all the characters to resuming their place in the community, even at the cost of abandoning their distinctive visions. We continue our examination of comedy with As You Like It and Twelfth Night and see how Shakespeare’s portrayal of romantic love relates to his portrayal of chivalry in the history plays. Rooted in both basic bodily impulses and artificial poetic ideals, romantic love as a topic allows Shakespeare to deal with the tension between nature and convention in human life.

We return to tragedy with perhaps Shakespeare’s greatest achievement in the genre: King Lear. Here the tension between nature and convention turns tragic, as Shakespeare poses the question: what is human nature and what is its relation to the political order? We conclude with one of Shakespeare’s last plays, The Tempest, which offers a retrospective on his career as a dramatist, harking back to motifs and themes from both his comedies and tragedies. The Tempest attempts to move beyond tragedy to a more comprehensive and philosophic position that shares affinities with comedy, while still transcending the conventional comic perspective.

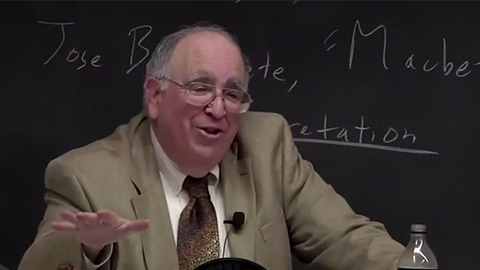

Seminar: Shakespeare’s Rome – Course Description

In this seminar, we study Shakespeare as a serious political thinker, who displays familiarity with Plato and Aristotle, and detailed knowledge of Machiavelli’s Discourses. Shakespeare’s Roman plays are a sustained effort to understand what he and his contemporaries regarded as the most successful political community in antiquity and perhaps in all of human history. The Renaissance was an attempt to revive classical antiquity; Shakespeare’s Roman plays are one of the supreme achievements of the Renaissance in the way that they bring alive the ancient city on the stage.

We study the plays, not in the order in which they were written, but in historical order. Coriolanus portrays the early days of the Roman Republic, indeed the founding of the Republic, if one recognizes the tribunate as the distinctively republican institution in Rome. Julius Caesar portrays the last days of the Roman Republic, specifically the moment when Caesar tries to create a form of one-man rule in the city, while the conspirators try to restore the republican order. The issue of Republic vs. Empire stands at the heart of Julius Caesar. Antony and Cleopatra portrays the early days of the Roman Empire, the emergence of Octavius as the sole ruler of Rome (he went on to become Augustus Caesar, the first official Roman Emperor).

The way Shakespeare arranged his three Roman plays suggests that he was centrally concerned with the contrast between the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. The Roman plays thus offer an opportunity to study the phenomenon Plato and Aristotle referred to as the regime (politeia)—the way a particular form of government shapes a particular way of life. From classical antiquity down to the eighteenth century and such thinkers as Montesquieu and the American Founding Fathers, Rome has been one of the perennial themes of political theory. Shakespeare’s Roman plays are his contribution to the longstanding debate about Rome, and also occupy a very important place in his comprehensive understanding of the human condition. The plays are evidence of the crucial importance of politics in Shakespeare’s view of human nature, as well as of his sense of the limits of politics.