Introduction to the Work of Plutarch

Plutarch’s writing comes down to us in two voluminous collections: the Moralia and the Lives. Both testify to Plutarch’s philosophical interest in human excellence, and both have won admiration from illustrious figures like Montaigne, Shakespeare, Rousseau, and the American founders. The two collections differ significantly, however, in form and content.

With the title “Moralia” Plutarch’s editors indicated what they took to be the central theme of the varied dialogues, treatises, and orations that have come down to us under his name. Plutarch himself did not conceive the Moralia as a single work. Some of his writings, like “On Moral Virtue” or “Controlling Anger,” seem nevertheless to fit easily under the heading of moral essays. Others, like “Whether Land or Sea Animals are More Intelligent,” take up topics in natural philosophy, or, like “The Obsolescence of Oracles,” theology. Even in these works, however, the traditional questions of political and moral philosophy are not entirely absent. In the dialogue on land and sea animals, for instance, interlocutors are asked to judge a contest among ambitious rhetoricians. Plutarch’s dialogues on the Delphic Oracle consider how the Greek cities’ subservience to Rome alters the form in which the gods reveal themselves.

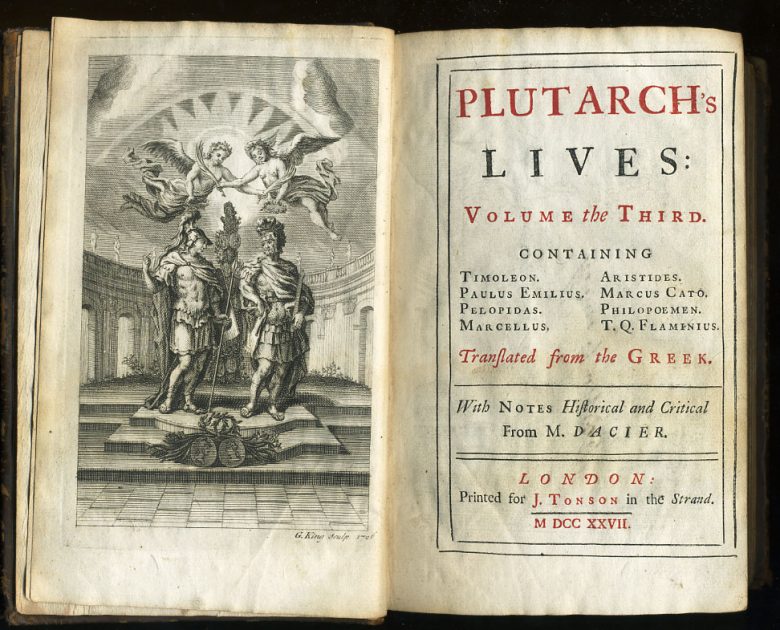

By contrast to the Moralia, the Parallel Lives were conceived as a single work, though parts have been lost and its precise scope is somewhat obscure. It is thanks to the Lives that James Boswell, in his Life of Johnson, dubbed Plutarch “the prince of ancient biographers.” Plutarch’s notion of biography differed in some important respect from our own (and Boswell’s). A Life’s intent was not historical so much as ethical: not to illuminate a particular individual, but to discover the universal qualities that inhered in an individual’s character, and thus invite the reader’s to blame, praise, and even emulate that individual. The individuals Plutarch selected for this purpose were all of them outstanding statesmen living in free cities. Among Plutarch’s protagonists there were no servants of the Empire, like Tacitus’s Agricola, nor were there literary figures like Boswell’s Johnson.

Plutarch’s corpus, taken as a whole, represents a sustained philosophical reflection on man’s place in the world that never loses sight of the importance of politics in human life.

Moralia

Several writings in the Moralia shed light on Plutarch’s approach to questions central to the tradition of ancient political philosophy, like the relationship between the active and contemplative lives.

In the “Precepts of Statecraft,” for instance, Plutarch offers advice to an ambitious young man eager to begin a political career in the Greek cities. Some of the advice Plutarch gives is timeless. The young man should consider carefully the character of the people he intends to lead; once in a position of power, he should lead by both example and speech. But Plutarch also offers a candid glimpse of imperial politics as seen from the periphery. The ambitious Greek statesmen must never forget, Plutarch cautions, that the cities are no longer free:

… you must say to yourself: ‘You who rule are a subject, ruling a state controlled by proconsuls, the agents of Caesar; ‘these are not the spearmen of the plain,’ nor is this ancient Sardis, nor the famed Lydian power.’ You should arrange your cloak more carefully and from the office of the generals keep your eyes upon the orators’ platform, and not have great pride or confidence in your crown, since you see the boots of the Roman soldiers just above your head.

Plutarch’s correspondent should thus speak cautiously of the battles in which the united Greek cities defended their freedom against the Persians, “and all the other examples which make the common folk vainly swell with pride and kick up their heels.” The Greek statesman’s goal under the Roman Empire is no longer victory in war – for “all war, both Greek and foreign, has been banished” – but maintaining domestic concord, good relations with the Romans, and “a life of harmony and quiet.” Even with the goals of politics seemingly so diminished from Greece’s glory days, however, Plutarch does not urge a life of contemplation on the ambitious young man, as Socrates had done with Alcibiades. Politics, no matter how paltry, remains the proper setting for virtuous action.

Praise of political virtue runs throughout the Moralia. In “Whether an Old Man Should Engage in Politics,” Plutarch argues that man is “intended by nature to live throughout his allotted time the life of a citizen,” never retiring into private life and never ceasing to love “his native land and fellow-citizens.” As with old men, so with philosophers. An essay titled “That a Philosopher Ought to Converse Especially with Men in Power” portrays philosophy, properly understood, as favorable to political action. The teaching of philosophy is not “‘a sculptor to carve statues doomed to stand idly on their pedestals and no more’;” rather, he “strives to make everything that he touches active and efficient and alive, it inspires men with impulses which urge to action, with judgements that lead them towards what is useful, with preferences for things that are honorable, with wisdom and greatness of mind joined to gentleness and conservatism.” In the same spirit, Plutarch contemns Epicurean sages for retreating to their private gardens and killing ambitious young men’s longing for “virtue and action.” The philosophers Plutarch most admires not only encourage virtuous action in their students but themselves engage in political life. Plutarch praises Plato for liberating Syracuse through Dion, Aristotle for freeing Stageira, and Theophrastus for overthrowing tyrants in his native Eresos.

Even in highly-wrought (and possibly youthful) rhetorical works, Plutarch is more concerned to synthesize the active and the contemplative than to separate them. In the “Fortune or Virtue of Alexander,” Plutarch praises Alexander as a philosopher, indeed more of a philosopher than those who left behind only writings. “Few of us read Plato’s Laws,” Plutarch writes, “yet hundreds of thousands have made use of Alexander’s laws, and continue to use them.” “Were the Athenians More Famous in War or Wisdom?” asks another oration. In war, Plutarch answers, for without the exploits of Athens’ statesmen and generals, what would Athens’ literary men have had to contemplate and commemorate in their works?

Parallel Lives

The Parallel Lives appears in the first instance to be just such a commemoration of great statesmen – a “bible for heroes,” as Emerson put it. But Plutarch did not intend these heroes to be worshipped, nor to be viewed at a distance, as one might admire a statue. Instead, the literary form of the Life, as Plutarch developed it, allowed him not only to record the actions of famous men, but to study their characters.

One of the most famous passages of the Lives expresses Plutarch’s intent:

It is not Histories that I am writing, but Lives; and in the most illustrious deeds there is not always a manifestation of virtue or vice, nay, a slight thing like a phrase or a jest often makes a greater revelation of character than battles when thousands fall, or the greatest armaments, or sieges of cities. Accordingly, just as painters get the likenesses in their portraits from the face and the expression of the eyes, wherein the character shows itself, but make very little account of the other parts of the body, so I must be permitted to devote myself rather to the signs of the soul in men, and by means of these to portray the life of each, leaving to others the description of their great contests.

Plutarch shows us Alexander on the battlefield, to be sure, but he also follows Alexander back into his tent. The result, for Plutarch’s reader, is a powerful sense of personal intimacy. One comes to know legends as only their closest companions could have done. (Elsewhere Plutarch compares the subjects of his biographies to men he has invited over for a dinner party.) The point of studying men like Alexander and Caesar at such close range, however, is not to record or to admire what is merely idiosyncratic to them as individuals. The goal is to study their soul, their character, their virtues and vices. Plutarch wants his readers to be students of human nature, eager to improve themselves based on what they learn. The Lives, then, are simultaneously records of individuals’ actions from birth to death, like our biographies, and “ways of life” to be studied, judged, and potentially imitated.

Plutarch arranged Lives, so conceived, in parallel. The Life of a Greek is always paired to the Life of a Roman, and Plutarch normally concludes the pair with a short “comparison” (synkrisis) of the two. (The 46 extant entries in the Parallel Lives are arranged in 22 pairs, one of which matches two Greeks with two Romans; 18 of the pairs conclude with a “comparison.”) While many had written lives before Plutarch, this way of presenting biographies in parallel is unique to him. It is worth considering why Plutarch made this innovation.

Pairing Greeks and Romans sets two great civilizations alongside one another as equals. It also serves to deepen Plutarch’s analysis of individual protagonists, allowing his readers to study Coriolanus, for instance, not only in isolation, but in comparison and contrast to Alcibiades. The short “comparisons” that conclude each pair, in which Plutarch generally argues for the superiority of each protagonist in turn, also serve to exercise and educate political judgment. Rather than being allowed merely to admire a diptych of heroes, the reader is given front row seats at a competition and asked to vote for a winner. Plutarch himself never decides who comes out on top. The point of his writing Lives in parallel is not to show that the Greeks are superior to the Romans or vice-versa, but to take advantage of how competitions can reveal the character of the competitors and exercise the readers’ capacity to form judgments about virtue. Deciding whether Alexander or Caesar is the better statesman requires us to consider what exactly we mean by “better” and to apply that understanding to particular cases.

Plutarch does not allow just anyone to enter these contests. We know from works in the Moralia, especially, that Plutarch admired poets and philosophers – in fact, he and his friends held annual birthday parties for Socrates and Plato. But even these philosophers (to say nothing of the Epicureans) play only supporting roles in his great work. Plutarch focuses his Lives on a particular character type, the statesman or political man. He also focuses on a specific chronological period. The statesman Plutarch calls the “last of the Greeks,” Philopoemen, witnessed the Greek cities fall finally under the sway of Rome, while Antony, the last of Plutarch’s Romans, saw the republic give way to Octavian’s empire. Plutarch’s Greeks live in autonomous cities, his Romans prior to the empire. The portraits Plutarch chose to include in his Lives suggest that he wanted his readers to contemplate the political life that preceded the Empire.

What did Plutarch intend his reader to learn? The lessons Plutarch offered were many and varied – as varied, perhaps, as political life itself. One sees in the souls of Plutarch’s statesman the immense power of political ambition, for good and ill. One learns to admire virtues like justice, while also witnessing its destructive excesses when not tempered by prudence and gentleness. One witnesses the excellence and hubris of the great, as well as the noble recalcitrance and persistent envy of the many. All of these were themes to which Plutarch returned as the individual Lives he composed required.

Overarching the individual portraits and pairs, however, was Plutarch’s understanding of the city. In part, Plutarch revealed this understanding through the Lives themselves. As Plato’s Republic proposed the city as an analogue to the soul, so Plutarch took the soul as his window to the city. But Plutarch also seems to have noticed a pattern in the rise and fall of cities, one that might even be described as a Life. In three cases – Athens, Sparta, and Rome – Plutarch offers Lives of founders and lawgivers, on the one hand, and Lives of statesmen who witness the fall of their regime. Brutus calls Cassius the “last of the Romans”; an unidentified Roman calls Philopoemen “the last of the Greeks.” A larger narrative, then, knits together the Lives of individuals: the story of the birth of cities in founding moments, expansion and conquest owing to the ambition of their leading statesmen, followed finally by decline and fall.

Plutarch seems not to have wanted to hasten Rome’s fall. Nor did Plutarch consider the transience of political excellence and the ultimate futility of political ambition adequate justification to abandon the active for the contemplative life. On the contrary, he seems rather to have hoped to sustain, through a literary resurrection of the ancient cities and their greatest statesmen, the virtues required for an ennobling form of politics, even under the subjection of Empire.

Conclusion

Like every writer of noble ambition or great vanity, Plutarch likely intended the Parallel Lives to be a “possession for all time” (as Thucydides said). And indeed he has found avid readers in conditions quite different from the ones in which he wrote – from Maximus Planudes’ monastic cell to the tent Alexander Hamilton kept as Washington’s aide-de-camp during the American Revolution.