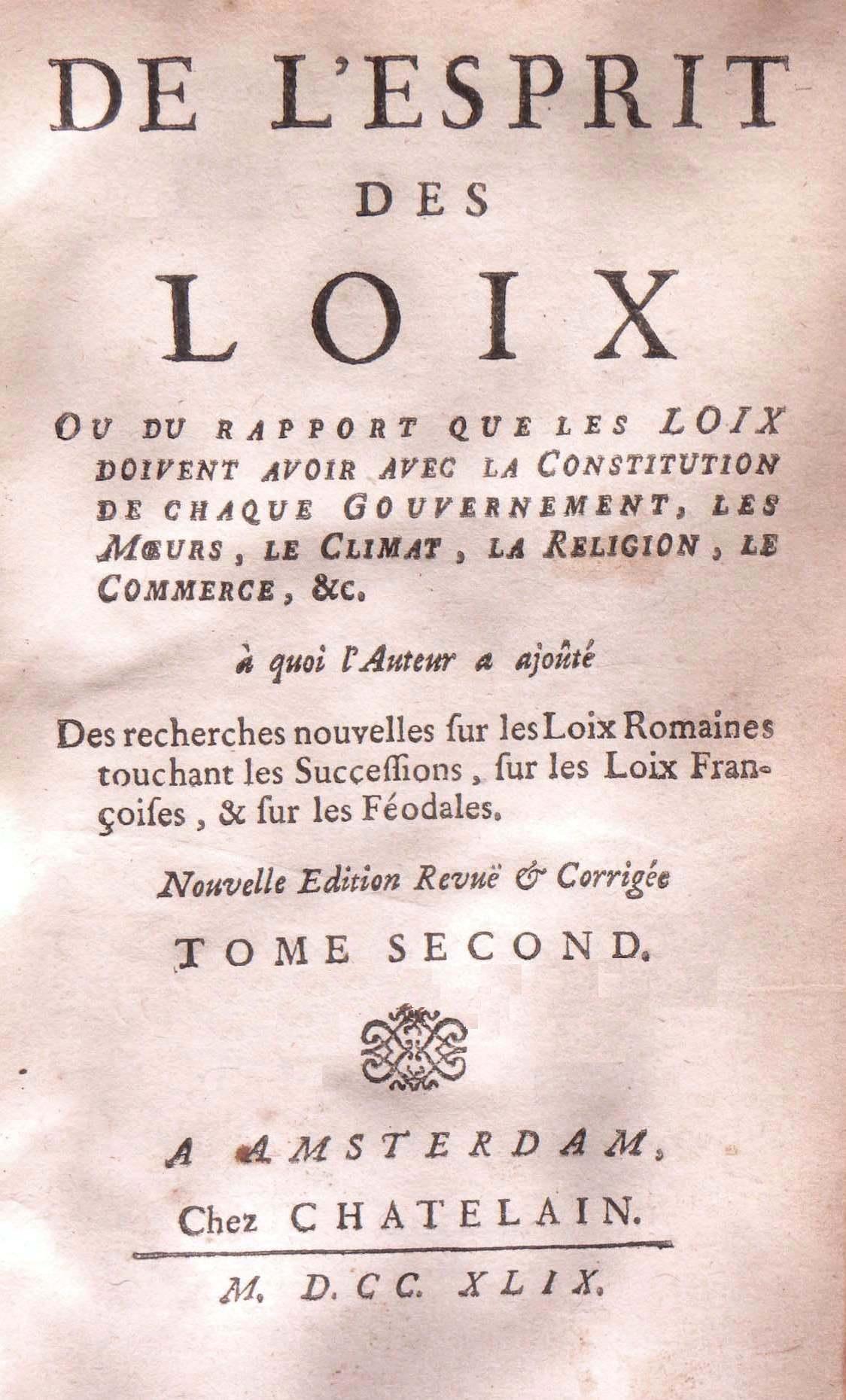

Recommended edition: Montesquieu, Charles de Secondat, baron de. The Spirit of the Laws. Edited and translated by Anne M. Cohler, Basia C. Miller, and Harold Stone. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989.

Excerpt from the recommended edition:

I began by examining men, and I believed that, amidst the infinite diversity of laws and mores, they were not led by their fancies alone.

I have set down the principles, and I have seen particular cases conform to them as if by themselves, the histories of all nations being but their consequences, and each particular law connecting with another law or dependent on a more general one.

When I turned to antiquity, I sought to capture its spirit in order not to consider as similar those cases with real differences or to overlook differences that appear similar.

I did not draw my principles from my prejudices but from the nature of things.

Many of the truths will make themselves felt here only when one sees the chain connecting them with others. The more one reflects on the details, the more one will feel the certainty of the principles. As for the details, I have not given them all, for who could say everything without being tedious?…

It is not a matter of indifference that the people be enlightened. The prejudices of magistrates began as the prejudices of the nation. In a time of ignorance, one has no doubts even while doing the greatest evils; in an enlightened age, one trembles even while doing the greatest goods. One feels the old abuses and sees their correction, but one also sees the abuses of the correction itself. One lets an ill remain if one fears something worse; one lets a good remain if one is in doubt about a better. One looks at the parts only in order to judge the whole; one examines all the causes in order to see the results.

If I could make it so that everyone had new reasons for loving his duties, his prince, his homeland and his laws and that each could better feel his happiness in his own country, government, and position, I would consider myself the happiest of mortals.

If I could make it so that those who command increased their knowledge of what they should prescribe and that those who obey found a new pleasure in obeying, I would consider myself the happiest of mortals.

I would consider myself the happiest of mortals if I could make it so that men were able to cure themselves of their prejudices. Here I call prejudices not what makes one unaware of certain things but what makes one unaware of oneself.

By seeking to instruct men one can practice the general virtue that includes love of all. Man, that flexible being who adapts himself in society to the thoughts and impressions of others, is equally capable of knowing his own nature when it is shown to him, and of losing even the feeling of it when it is concealed from him….

If this work meets with success, I shall owe much of it to the majesty of my subject; still, I do not believe that I have totally lacked genius. When I have seen what so many great men in France, England, and Germany have written before me, I have been filled with wonder, but I have not lost courage. “And I too am a painter,” have I said with Correggio.

Online:

Online Library of Liberty- Volume I (Free version)

Online Library of Liberty- Volume II (Free version)

Amazon (Recommended edition)