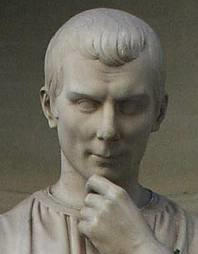

Biography

Niccolò Machiavelli was born in Florence on May 3, 1469, to Bernardo and Bartolomea. Though the family had formerly enjoyed prestige and financial success, in Niccolò’s youth his father struggled with debt. Nevertheless, his father was actively interested in education and provided young Niccolò with access to books.

The world of Machiavelli’s youth was one of great ferment in matters political, intellectual, and ecclesiastical. Florence was among the many Italian city-republics frequently contested by the larger political powers of the day—the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire, along with France and Spain. New editions and translations of classical Greek and Roman texts provided the material for the intellectual movement known as the Renaissance, which combined an interest in Christianity with a newfound curiosity about classical culture. Meanwhile, although the Church had always been important politically in Europe, in Machiavelli’s time the Church’s involvement in worldly politics included its direct participation in wars of acquisition.

Florence had risen to prominence as a banking center, and the Medici banking family had been the effective rulers of Florence since 1434. Machiavelli’s youth saw a failed attempt on the Medici dynasty by the Pazzi family in 1478, in addition to the dramatic rise of the Dominican friar Savonarola. When Machiavelli was twenty-five, Charles VIII of France invaded Italy, and the subsequent departure of the Medici family left Florence in the hands of Savonarola. After a tumultuous rule of under four years, Savonarola was executed, and Piero Soderini reestablished republican government.

It was under Soderini’s republic that Machiavelli, now almost thirty, became Second Chancellor of the Florentine Republic, an important position involving both internal and diplomatic duties. After the restructuring of the republic in 1502 and the subsequent appointment of Soderini as gonfaloniere, Machiavelli’s influence grew. He undertook diplomatic missions to many of the great European powers and worked intensely to improve the Florentine militia. In doing so he made not a few enemies.

Machiavelli was married from 1501 till his death, with his wife Marietta bearing seven children. His extramarital activities were occasionally a source of scandal.

1512 saw the restoration of Medici rule after Cardinal Giovanni de Medici, soon to be elected Pope Leo X, reconquered Florence along with Pope Julius II. Machiavelli was removed from office in the change of regime and was arrested for conspiracy against the Medici.

Machiavelli produced his most important literary and political writings during the subsequent years when he retired to his estate outside Florence, while not abandoning his political ambitions. His first work, The Prince, which he finished toward the end of 1513, carries a dedication to Lorenzo de’ Medici—perhaps reflecting Machiavelli’s hopes of returning to political life. Around the same time he was also composing his Discourses on Livy, a larger undertaking not finished till 1517 at the earliest. Neither political treatise, however, was published in his lifetime; the Discourses reached print in 1531, The Prince in 1532.

Following 1513, Machiavelli continued to exercise his literary skills. His Golden Ass, though never completed, was written in 1517, followed in the subsequent year by his comedy Mandragola. At the beginning of the 1520s Machiavelli brought out his Life of Castruccio Castracani (1520), was commissioned by the Medici to write his Florentine Histories (published 1525), and published his Art of War (1521).

After the defeat of Florence by the Holy Roman Empire in 1527, a new Florentine Republic was declared. Just over one month later, Machiavelli died. His political legacy, however, had just begun.

For further biographical reading, see also:

Cambridge Companion to Machiavelli, Ed. John Najemy, Cambridge: 2010.